Partying like it’s 1899

Wealthy Americans are still enjoying the fruits of others’ labor in a system economist Thorstein Veblen described 125 years ago.

Yes, the title is a play on Prince’s 1982 hit song “1999.” His lyric “parties weren’t meant to last” sums up my message regarding the folly of America’s monetary and fiscal policies. That message, which I have repeated at every opportunity in my writing, is reinforced by noting how our nation’s elite have managed — at tremendous cost to our most vulnerable citizens — to keep the Gilded Age party going for about 150 years.

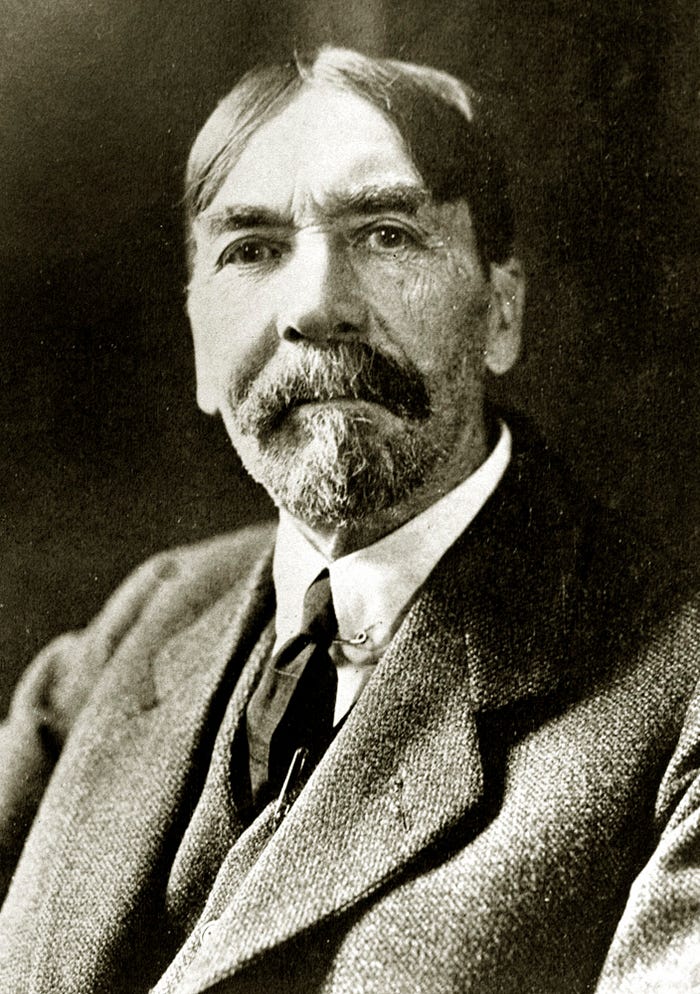

If you follow me, you cannot miss the anti-establishment theme in my writing. I’m a late bloomer, having identified as an independent voter in the 1990s (my late thirties) and a heterodox economist in the oughts. I had just begun graduate school (2001) when a friend gifted me a vintage (1928) copy of The Theory of the Leisure Class. It didn’t fit into my studies, but I enjoyed it then and never forgot the story of how social classes emerged in our “land of opportunity.” A recent post by one of my favorite writers on Medium, Greg Daneke, inspired me to reread it. The density of Veblen’s prose can be challenging. However, his detailed descriptions of class awareness, motivations, and forces are very interesting and worthwhile because they are still relevant.

I took quite a few notes and am further inspired to connect Veblen’s observations about modern values with the very large and growing income inequality in the US that I wrote about in A Moral Economy. Thanks to another Medium writer who provided a very good summary of the book that notes similarities and differences between the leisure classes of the fin de siècle era and our own [1], I can focus on policy analysis.

Two salient points in this book help explain why income inequality is such a persistent feature of our economic system.

First of all, the distinction of wealth is more desirable than its direct benefits. For this reason, desire for wealth is insatiable. Also, virtually everyone enjoys improved living standards and many emulate those who seem to be doing better by living beyond their means. Ambitious individuals take on predatory and pecuniary habits and aptitudes prevalent in the upper class.

Veblen harps on the economic waste of conspicuous leisure and consumption. Anyone may (legally) spend their time and money as they wish; however, these practices do not benefit society. And he presents compelling arguments that they do actual harm by exploiting others and by the corrupting moral and economic influence of encouraging lower class emulation. This supports my contention that good public policy would discourage gratuitous accumulation of wealth.

Secondly, the wealthy naturally become conservative because they are sheltered from economic forces that cause institutional change:

Under the circumstances prevailing at any given time [the leisure] class is in a privileged position, and any departure from the existing order may be expected to work to the detriment of the class rather than the reverse.

Lower classes become conservative only because they are too busy struggling for daily subsistence to think about the long term and invest the effort necessary to enact change.

Veblen says nothing about politics. I have plenty to say about it, and to this point it’s important to recognize that “conservative” in this context does not imply any particular party. Indeed, our current Presidential election is evidence of bipartisan support for the institutions and policies that favor protection of wealth. Neither major party candidate poses any threat to raising taxes that could erase our trillion dollar annual deficits and put major entitlements on a path to solvency. Money has a death grip on our electoral system.

The working class (most of us) need political power (equality at the ballot box) to increase our economic power. Unfortunately, while the the ruling class (aka leisure class) in the US is perfectly satisfied with the status quo, the working class is decidedly not. Yet we don’t appear to have any real choice in most elections and especially the race for President in 2024. How did it come to this? The same way we got high income inequality. As Veblen noted, while we’re busy making a living, the ruling class erects and maintains barriers to change. Today, that mechanism is the duopoly of two major political parties. Instead of listening to voters, politicians tell us who to choose.

It may not work this time. Independents may not “lean” either way, and disappointed partisans with no viable alternative may stay home. It may get ugly, but maybe an election that defies the polling data and manipulation by rent-seekers is what we need to snap out of our induced coma.

Regardless of the outcome of this election, we have a ton of work to do, especially at the state level, to reverse the polarization that has divided us into red and blue states and invited a host of additional anti-democratic shenanigans. The parties can hardly be more powerful and have shown they will not yield anything without a fight. However, as I noted at the end of my last post, momentum for election reforms such as nonpartisan primaries, ranked choice voting, and multi-member districts are building, thanks to ballot initiatives in a number of states that could get traction with voters and a few forward-looking politicians who have proposed bold legislation on our behalf.

Real democracy that places political power in voters’ hands will offer opportunities to weaken the class system described by Veblen that rewards predatory and pecuniary pursuit of wealth.

As I’ve explained in prior essays, increasing income inequality is a direct result of monetary and fiscal policies that favor capital over labor. We can and should promote a truly free market by removing all of them. At the same time, we should make restitution by creating a real safety net for all Americans:

Inflation is an explicit goal of the Federal Reserve Bank that is encouraged by cheap loans to capitalists at the expense of consumers. At the very least, we should aim for zero inflation of consumer prices (vs. the current 2 percent target).

Payroll taxes have replaced corporate income taxes as a source of federal revenue over the last half century. How does that make sense? The payroll tax is highly regressive and discourages work; it should be eliminated. We can fund existing Social Security and Medicare obligations by eliminating tax expenditures (deductions from income) and raising marginal income taxes.

Work requirements for public assistance are not effective in reducing poverty and should be eliminated.

Adopt a federal basic income guarantee at the poverty level ($15,000/year) for every adult citizen. Fund it with additional income taxes on wealthy households. A negative income tax design will maintain work incentives and provide a form of social security that gives wage earners control over their savings and access to help when they need it.

These reforms will reduce the gap between incomes of wealthy and poor households in the US. More importantly, they will significantly reduce incentives for (conspicuous) accumulation by the wealthy and increase financial security for the poor. Over time, perhaps the selfish attitudes identified by Veblen will fade away. We will be happier if they do.

[1] For example, in the Gilded Age and prior eras, wealthy people employed (or owned) servants and industrialization had not yet evolved a large class of what we now refer to as “white collar” workers. Actual labor was easily identified as such. Today, we have a meritocracy in which many people become rich by managing businesses and working long hours. Conspicuous consumption is very strong; conspicuous leisure, not so much.